by Lucian Cristian Ratoiu — Published on October 9, 2025 — Reading time: 18 min

Article sections

» Colors and commercial development » Home manufacture of watercolors » Brushes and other tools » The importance of watercolor paper » Some notes on watercolor techniques » Further reading and resources

This article explores the material evolution of watercolor and how technical innovation shaped its artistic development. Beginning with William Reeves’s late-eighteenth-century color cakes and continuing through Winsor & Newton’s nineteenth-century pans and tubes, it traces the transition from hand-ground pigments to standardized, machine-milled paints. It explains the relationship between pigment, gum Arabic, and paper—how watercolor functions as a stain within the paper fibers, how sizing and surface affect transparency and control, and how opaque pigments can be rendered luminous through thin application. The discussion concludes with an overview of brushes, portable kits, and paper types, connecting historical practice to modern materials and techniques.

Colors and commercial development

The emergence of watercolor as a serious artistic medium developed in tandem with improvements in its materials. Until the late eighteenth century, artists ground their own pigments or purchased liquid colors. This changed with William Reeves’s 1780 invention of small, soluble color cakes, which allowed artists to prepare paint quickly and work outside the studio. Beginning in the 1830s, artists could buy moist watercolors in porcelain pans. An even greater advance arrived in 1846, when Winsor & Newton introduced moist watercolors in metal tubes (following the example of tubed oil paint, first sold in 1841). The machine-ground pigments pioneered by British manufacturers produced fine, homogeneous watercolors that set the international standard.

In 1834, Winsor & Newton introduced their patented zinc oxide pigment “Chinese White”; this superfine—and therefore smoothly applied—permanent color greatly improved the qualities of gouache. In the first half of the nineteenth century, J. M. W. Turner instituted the practice of applying diluted white gouache as a wash. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Pre-Raphaelite painters used white gouache as a ground upon which to paint in a precise, miniature-like style.

As Ralph Mayer observed, nearly all permanent pigments approved for oil painting can also be used in watercolor—except those containing lead, such as flake white and true Naples yellow. Transparent pigments like cobalt yellow, alizarin, and manganese blue yield the most brilliant washes, while opaque colors such as the cadmiums can appear transparent when applied in thin, lightly pigmented layers.

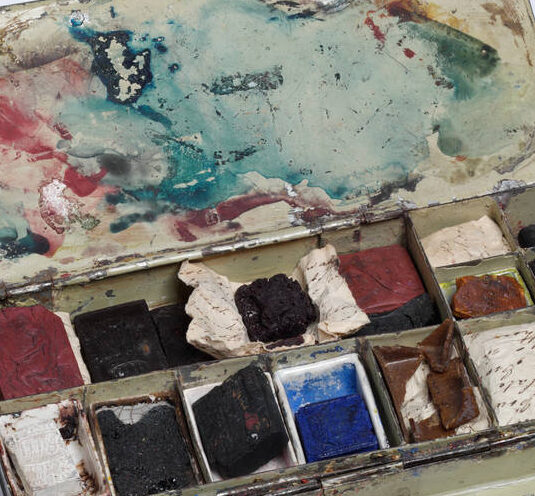

By the mid-eighteenth century, British artists regularly worked outdoors, drawn to watercolor’s portability and responsiveness to light and weather. Compact color boxes—ranging from handcrafted ivory and leather cases to Victorian “shilling boxes”—made sketching from nature both practical and fashionable, fueling watercolor’s popularity among professionals and amateurs alike.

Watercolor paints consist of finely ground pigments dispersed in gum Arabic, producing a medium that can be heavily diluted yet still adhere to paper. The interaction between paint and paper is fundamental: rather than forming a solid film, watercolor stains the fibers of its support. This quality underlies the medium’s luminosity but also its fragility—thick or impasto applications, as in gouache, rely more on the binder, and may tend to crack especially if the support is not rigid. When lightfast pigments are used on high-quality rag paper and stored under proper conditions, watercolor is as durable as any other painting medium (fading occurs only in colors made from fugitive pigments, not because watercolor films are thin).

The watercolor palette comprises a vast range of pigments. These include colors made from natural minerals, resins, or vegetables; for example, earths (such as ocher and burnt umber), azurite, madder root, and gamboge. Artificial colors processed from minerals include Prussian blue, vermilion, lead white, and cadmium yellow. Starting in the late nineteenth century, manmade organic colors were synthesized in laboratories to produce brilliant hues that range from oranges to violets and mauves.

Home manufacture of watercolors

Few artists today attempt to make their own watercolors, as modern commercial paints offer high quality and consistency. Historically, however, some painters prepared their own colors through experimentation and careful adjustment of ingredients. Each pigment required a specific proportion of binder to achieve the right balance of solubility, adhesion, and workability.

The main challenge in homemade paints was fine grinding—a process nearly impossible to replicate outside industrial roller mills, which produced the smooth, homogeneous dispersions found in professional paints. Hand-ground colors often appeared grainy, lifted too easily, or lacked brilliance.

Gouache paints, being more opaque and forgiving, could be made more successfully in the studio. Once the vehicle was prepared, pigments were ground with the solution into a smooth paste, then dried into pans or stored moist in small containers. Distilled water was preferred to avoid mineral deposits or discoloration.

| Gum Arabic | Primary binder and adhesive; too much creates a hard, glossy surface. |

| Glycerin or Honey | Retains moisture, improves flow, prevents cracking; excess causes over-solubility. |

| Sugar Syrup / Glucose | Acts as a plasticizer, improving smoothness. |

| Wetting Agent | Reduces surface tension, allowing even washes (modern substitutes have replaced ox gall). |

| Preservative | Prevents mold growth (modern non-toxic agents replace older phenol compounds). |

| Optional: Oil of Cloves | Light fragrance and mild preservative effect. |

Watercolors were originally sold as dry, compressed cakes, but these have largely been replaced by pans and tubes containing moist paints. Tubes are now the most popular form because of their convenience. A few painters, however, still prefer the traditional dry cakes for their cleanliness and purity. The dry cakes are made with a medium composed of concentrated gum Senegal, a small amount of ox gall, and occasionally sugar. Sugar acts as a plasticizer, allowing the color to be brushed out more smoothly. Like glycerin, it also increases the solubility of the dry paint. However, excessive sugar can upset the formula, making the paint too easily lifted during overpainting or other manipulations.

Watercolors differ from oil or tempera paints in that they dry purely by evaporation rather than chemical change. As a result, dried paint can always be re-wet and reused, whether in pans, cakes, or even hardened tubes. This reversibility makes watercolor one of the most flexible and enduring painting media. Because modern manufacturers grind pigments to microscopic fineness and control binder ratios precisely, contemporary artists benefit from a consistency that early practitioners could only approximate. Handmade paint remains a valuable educational exercise but is rarely practical for sustained artistic use.

Brushes and other tools

The ideal watercolor brush combines spring, absorbency, and a fine point—qualities best achieved with Asiatic marten (or Russian sable) hair. These brushes hold a generous charge of color, release it evenly, and return naturally to a point, allowing both delicate lines and fluid washes. Early brushes used quill handles, later replaced by wooden handles with metal ferrules for durability and control.

During the nineteenth century, artists expanded their toolkits as reductive techniques gained popularity. Painters used scrapers, penknives, sandpaper, or even fingernails to lift pigment and create highlights, while sponges, blotting paper, or bread crumbs softened or erased passages. These simple implements offered remarkable control over tone and texture, enabling effects that ranged from atmospheric veils to sharp illumination. Modern watercolorists continue to use a variety of specialized brushes—rounds, flats, mops, riggers, and fans—each suited to different textures and applications. Synthetic fibers now supplement natural hair, offering ethical and economical alternatives while preserving much of the traditional responsiveness prized by painters.

The importance of watercolor paper

The history of watercolor paper reflects centuries of experimentation with materials and methods. Early European artists painted on papyrus, parchment, and vellum, later transitioning to linen-based papers introduced in the thirteenth century. The best watercolor supports were made from pure linen rag, free of chemicals and metal residues, producing a durable and brilliantly white surface.

Asian artists developed equally refined materials. Chinese and Japanese papers, traditionally made from mulberry bark, met the needs of calligraphy and painting but tended to darken and become brittle over time. Their sizing—usually animal glue hardened with alum—gave them distinctive absorbency and softness.

A major innovation occurred in eighteenth-century Britain with the invention of wove paper, which replaced the ribbed texture of laid paper with a smooth surface ideal for even washes. Around the 1780s, James Whatman perfected a gelatin-sized wove paper specifically for watercolor. This allowed artists to layer color and lift washes without damaging the surface.

Throughout the nineteenth century, manufacturers such as Whatman, J. Barcham Green, and later Fabriano introduced papers of varying textures, weights, and strengths. To prevent buckling under wet washes, artists began stretching dampened sheets—first by pinning or pasting them to boards, and later using dedicated stretching frames or pre-glued watercolor blocks.

Paper’s absorbency and resilience are crucial to watercolor’s character. It must be strong enough to withstand repeated wetting yet not so absorbent that colors sink and lose brilliance. High-quality watercolor paper is made from cellulose fibers (ideally 100% cotton or linen) and pure water. Cotton papers offer strength, flexibility, and resistance to yellowing, while wood pulp papers deteriorate quickly. Most professional papers are acid-free and buffered with calcium carbonate, ensuring long-term stability. The surface is treated with gelatin sizing to regulate absorbency—too little sizing causes dull, sunken washes; too much prevents proper flow.

Papermaking itself remains a blend of art and industry. Handmade and mould-made papers, such as those by Whatman, Fabriano, and Saunders Waterford, use carefully prepared pulp mixed with pure water and internal sizing. Linen-based papers remain the most durable and responsive, while cotton rag papers—though slightly softer—offer excellent performance for modern use. Inferior machine-made or wood-pulp papers tend to yellow, weaken, and absorb color unevenly. For consistent results, artists should work on acid-free, 100% cotton papers of at least 140 lb (300 gsm) weight, preferably gelatin-sized and calcium-buffered.

| Fiber | 100% cotton (rag); cotton blends; wood-pulp | Fiber length & purity affect strength, longevity, color brilliance | Cotton: durable, bright, resilient to scrubbing | Wood-pulp yellows/brittles; blends vary |

| Manufacture | Handmade; Mould-made; Machine-made | Fiber orientation & surface character | Handmade/mould-made: random fibers → strong, lively surface | Some machine-made papers feel “mechanical” |

| Sizing (internal/surface) | Gelatin/hide glue; modern variants; unsized | Controls absorption & lift | Balanced sizing = crisp strokes + luminous washes | Over-sized → beading; under-sized → sinking/dullness |

| Surface | HP (Hot-Pressed) smooth; NOT/CP mid-tooth; Rough high tooth | Dictates detail, edges, texture | HP: detail/line; CP: versatile; Rough: texture/granulation | HP can feel slippery; Rough reduces fine detail |

| Weight | ~190–300 gsm (90–140 lb); 300–425 gsm (140–200 lb); 640–850+ gsm (300–400 lb) | Heavier = less cockling, more rework | Heavy sheets tolerate scrubbing; often no stretching | Light weights demand stretching; cockle easily |

| Formats | Sheets (e.g., Imperial 22×30 in, Antiquarian 31×53 in); Blocks; Rolls | Workflow & portability | Blocks: no stretching; sheets: flexible sizes | Blocks cost more; rolls need cutting & storage |

| Tone/Color | Bright white; natural white; tinted | Affects perceived chroma and value | Warm/natural whites soften palettes | Tinted papers limit maximum “white” highlight |

| Conservation | Acid-free; buffered; OBA-free | Long-term stability, color fidelity | Buffered cotton resists acid migration | OBAs can shift tone under UV; avoid poor storage |

Some notes on watercolor techniques

Watercolor painting encompasses a wide range of methods and schools. Most modern painters do not adhere strictly to a single technique but instead adopt any manipulation that suits their artistic purpose. As a medium for serious and complete works of art, watercolor gained prominence in early nineteenth-century England. The traditional English method involved building up thin, transparent washes of delicately mixed color, one over another, until the desired depth and tone were achieved—usually over a carefully executed pencil drawing.

While countless manuals have been written on watercolor practice, contemporary artists tend to favor more direct and expressive methods, emphasizing spontaneity and clarity of tone over laborious layering.

According to Max Doerner, preliminary drawings should be made lightly, with minimal erasing, to preserve the paper’s surface and ensure it will accept color evenly. The sheet is lightly dampened with a sponge; painting begins once the sheen of surface water disappears. Only water should be used as the painting medium. A restricted palette enhances harmony: most tones can be derived from Indian yellow, madder lake, Prussian blue, and transparent chromium oxide, with few additions required. Confident artists can apply color boldly and directly—working from shadows toward the light, tone beside tone—maintaining freshness and avoiding overworked, dull passages.

In earlier practice, artists began with pale, neutral tones and gradually strengthened them through multiple washes. By allowing colors to blend and run together, they achieved soft transitions and a decorative, harmonious effect. Highlights were left as unpainted paper or lifted out from wet color using a brush, chamois, or eraser—methods that produced gentle, luminous accents. When color is applied to a surface that is too dry, it forms sharp edges, which can be exploited deliberately for expressive effects. Following the precedent of the Dutch painters, many modern artists combine transparent watercolor with touches of opaque white, applied on half-dry or dry surfaces to create airy or bodycolor effects. The beauty of watercolor lies in its soft, bright tonal range and its ability to convey lightness and immediacy.

Some painters have experimented with applying thin varnishes—such as diluted Zapon varnish or shellac fixatives—to deepen shadows, though such coatings should be tested and generally avoided, as they may alter the color surface undesirably.

Ivory as a painting support: Ivory was occasionally used as a support for miniature painting. It tends to yellow over time, a process that can be reversed by treatment with hydrogen peroxide applied between dampened blotting papers. Because ivory is sensitive to grease, it must never be touched directly; any contamination should be removed with benzine, dilute ammonia, or ox gall. The surface is prepared by scraping and polishing with fine pumice and water, then dried under even pressure. Paint is applied wet-in-wet, from top to bottom, avoiding overly fluid washes that may cause edges. Some historical miniatures used oil colors applied to the reverse side of the ivory, producing a translucent glow when viewed from the front; others used silver foil behind the sheet to heighten brilliance.

General practice: The overall effect of a watercolor should remain light, loose, and fresh. Bleeding pigments—such as coal-tar dyes, alizarin madder lake, zinc yellow, and Indian yellow—should be avoided, as they penetrate the paper. If a tone becomes too heavy, it can be lightened by scraping with a blade or gently lifting pigment with a damp brush or needle. Work should begin with the simplest glazes, using a damp but well-pressed brush, never overloaded with paint. Reds, especially in flesh tones, are best reserved for final touches. Some painters recommend lightly coating the paper with a weak alum and glycerin solution to encourage a freer, broader technique.

Watercolor often combines effectively with charcoal, pencil, or pastel. When overpainting drawn lines, a light spray of archival fixative prevents smudging. Soft pastels may be applied over dry watercolor, especially on rough papers that provide sufficient tooth. Modern fixatives are flexible, non-glossy, and compatible with most media.

Gouache: In density of tone, gouache surpasses transparent watercolor, producing soft, opaque effects similar to pastel. It allows greater freedom and control, using the same gum or glue binders but with added white fillers such as barite or clay. Gouache performs best on colored grounds or tinted papers, which harmonize its more opaque tones. Round bristle or soft hair brushes may be used. Painters often begin with thin applications, strengthening them gradually and setting lights opaquely in nearly dry strokes. This yields a unified, luminous effect characteristic of the technique. Gouache can be rendered water-resistant by spraying with 4% gelatin, followed by a 4% formalin fixative.

Gouache has largely been supplanted by tempera and poster colors—glue-based paints containing substantial fillers that cover uniformly. When sprayed with formalin they become water-insoluble, though gum-based varieties remain reversible.

Wet and dry techniques: Traditional methods often employed successive transparent washes to build luminous skies or atmospheric effects. The process involved multiple layers of thin color, each partially lifted with blotting paper before the next wash was applied, producing a sparkling brilliance.

Another approach paints directly on thoroughly wet paper, producing soft outlines and diffused transitions. The paper is soaked until near saturation, then secured to a shellacked board or glass plate to maintain moisture. For extended work, it can be mounted with hide glue on heavy cardboard and soaked overnight to retain dampness.

A variant, influenced by Impressionist practice, leaves narrow white gaps between color strokes to create mosaic-like vibrancy. Once dry, these spaces may be glazed to unify the composition.

Today, artists generally distinguish between two principal modes—the wet method and the dry method—depending on whether the paper is soaked, dampened, or entirely dry. The most common contemporary approach employs direct, confident strokes on dry or lightly moistened paper, refreshed as needed by gentle sponging or misting. Sheets are fastened to drawing boards with clips or tape, or, for greater precision, stretched taut when lighter papers are used. Finished works usually flatten naturally once dry and properly stored.

From pigment chemistry to paper texture, every element of watercolor contributes to its distinctive luminosity and expressive range. The refinement of color manufacturing, the evolution of brushes and tools, and the production of ever more sophisticated papers transformed watercolor from a convenient sketching aid into a mature artistic medium.

Further reading and resources

Andrew Wilton, Anne Lyles, The Great Age of British Watercolours 1750-1880, Prestel 1997.

Andy Griffiths, A – Z Glossary of Watercolor Terms (With Pics), https://www.solvingwatercolour.com/a-z-glossary-of-watercolor-terms-with-pics/

Bernard Brett, A History of Watercolor, Deans International Publishing, London,1984.

Carol Armstrong, Cezanne in the Studio. Still Life in Watercolors, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2004

David Cox, A Series of Progressive Lessons Intended to Elucidate the Art of Landscape Painting in Water-Colours, Published by T. Clay, London, 1816

Dorling Kindersley, Artist’s Painting Techniques: Step-By-Step Workshops from professional artists, DK, New York, 2016

Elizabeth E. Barker, Watercolor Painting in Britain, 1750–1850, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2004 https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/watercolor-painting-in-britain-1750-1850

Greg Smith, Thomas Girtin (1775–1802): An Online Catalogue, Archive and Introduction to the Artist, The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (PMC), https://www.thomasgirtin.com/

Hardie, Martin. Water-Colour Painting in Britain. 3 vols. London, 1966–68.

History of Modern Watercolor An on-line presentation to Fabriano in Watercolor 2020 https://inartefabriano.it/2020whistory.pdf

https://zam.umaine.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/96/2013/09/WatercolorGlossary.pdf

J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/jmw-turner

Jean-Louis Morelle, Watercolour Painting. A Complete Guide to Techniques and Materials, New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd London, 2003

John Berger, Albrecht Dürer: Watercolours and Drawings, Taschen, 1997.

Jose M. Parramon, The Big Book of Watercolor Painting.The history, the studio, the materials, the techniques, the subjects, the theory and the practice of watercolor painting, Watson – Guptill Publications, New York, 1985.

Marie-Pierre Salé, Watercolor: A History, Abbeville Press, 2020,

Max Doerner, The Materials of the Artist and Their Use in Painting, With Notes on the Techniques of the Old Masters, Chapter VII-Painting in Water Colors, pp. 255-273, Translated and revised by Eugen Neuhaus. Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., New York, Paperback reprint, 1984.

Pip Seymour, The Artist’s Handbook. A complete professional guide to materials and techniques, Arcturus, London, 2003.

Ralph Mayer, The Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques, The Viking Press, Third Edition / Revised and Expanded, New York, 1970, pp.293-304

Rawlinson, W. G., Finberg, A. J, Holroyd, C., The water-colours of J. M. W. Turner, National Gallery, Offices of ‘The Studio, London, Paris, New York, 1909

Rutherford J. Gettens & George L. Stout, Painting Materials. A Short Encyclopaedia, D. Van Nostrand Company. Inc, New York, 1947, p.77.

Thomas Rowbotham, T.L. Rowbotham, The Art of Landscape Painting in Water Colors, Winsor and Newton, London, 1850.

Watercolor, https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/drawings-and-prints/materials-and-techniques/drawing/watercolor

Wilton, Andrew, and Anne Lyles. The Great Age of British Watercolours, 1750–1880. Exhibition catalogue. Munich: Prestel, 1993.

Zillman Art Museum-University of Maine (ZAM), Glossary of Watercolor Painting Terms.

How to cite this resource

Ratoiu, L.C. (2025). A brief history of watercolors. Part II: Materials and techniques. INFRA-ART Blog